Becoming America’s Team, the Saints made us proud— of our franchise and of our city Vince Lombardi once said that his teams never truly lost, they just ran out of time. So it was with the New Orleans Saints on January 21 at the end of their 40th season. Chicago, a city that had seen its football teams play in sixteen NFL or NFC championships since 1932, was meeting a franchise from a city that had never played a single one but wanted it more than any Chicagoan could possibly understand.

Vince Lombardi once said that his teams never truly lost, they just ran out of time. So it was with the New Orleans Saints on January 21 at the end of their 40th season. Chicago, a city that had seen its football teams play in sixteen NFL or NFC championships since 1932, was meeting a franchise from a city that had never played a single one but wanted it more than any Chicagoan could possibly understand.

The 39–14 Bears’ victory would not tell the full tale, as the score was a fairly close 16–14 near the end of the third quarter with the Bears leading. And that was when the Saints tried to take it from them with a 47-yard field goal. There has been some talk among Saints fans and commentators regarding the lack of rushing attempts (merely 12 for the Saints compared to the Bears’ 46), but a look at the key plays in the game makes clear that the game plan was not at the source of the team’s loss.

In the first quarter, after moving the ball via the pass to near the Bears’ 30 within fair distance of an early strike, the Saints took a sack from the right side of the line, killing that drive (this was followed by a 16-yard net punt by Steve Weatherford). On their next series, the Saints again used the passing game and moved quickly into Bears’ territory, but again allowed a sack on Brees from the left side of the line, resulting in a fumble that led to a 25-yard loss (followed by a 26-yard net punt). And on their following series after moving the ball by air, the Bears’ defense yet again forced a mistake by causing Marques Colston to fumble; that error directly led to a short Bears drive and a 3–0 deficit. On the ensuing kickoff, a poor officiating call magically conjured a Mike Lewis fumble where there had been none and confirmed it on replay by yet another poor call (Sean Payton could clearly be seen mouthing “You missed it!”). The play resulted in a 6–0 differential.

In the first quarter, after moving the ball via the pass to near the Bears’ 30 within fair distance of an early strike, the Saints took a sack from the right side of the line, killing that drive (this was followed by a 16-yard net punt by Steve Weatherford). On their next series, the Saints again used the passing game and moved quickly into Bears’ territory, but again allowed a sack on Brees from the left side of the line, resulting in a fumble that led to a 25-yard loss (followed by a 26-yard net punt). And on their following series after moving the ball by air, the Bears’ defense yet again forced a mistake by causing Marques Colston to fumble; that error directly led to a short Bears drive and a 3–0 deficit. On the ensuing kickoff, a poor officiating call magically conjured a Mike Lewis fumble where there had been none and confirmed it on replay by yet another poor call (Sean Payton could clearly be seen mouthing “You missed it!”). The play resulted in a 6–0 differential.

Still yet another officiating decision based on flimsy evidence led to a rare offensive pass interference call on Terrance Copper that further pushed the Saints into a hole within their 15-yard line. The result was a short 34-yard net punt that led to another short drive and field goal by the Bears, leaving the Saints trailing 9–0. After again moving downfield to retake the field position advantage, the Saints managed only a 29-yard punt, leaving the Bears enough breathing room to allow them to manufacture 49 yards primarily in three plays by Thomas Jones for a 16–0 lead. The Saints’ two touchdowns were the result of virtuoso clutch passing by Drew Brees. One was a brilliant display of the two-minute drill resulting in a TD connection to Colston, a 73-yard drive executed in less than a minute. The second touchdown might fairly be called the second-best Saints play ever (after the River City Miracle), given the substance of the game and the perfect timing involved—an exceedingly well-thrown ball by Brees to Reggie Bush who proceeded to stretch the field past a horde of chasing defenders, for 88 yards—the longest ever in NFC Championship play. The Saints’ defense then produced a sturdy three-and-out stand against the Bears’ offense looking to answer quickly. Surely, at that point, the momentum and the game seemed to be falling into the Saints’ favor.

Still yet another officiating decision based on flimsy evidence led to a rare offensive pass interference call on Terrance Copper that further pushed the Saints into a hole within their 15-yard line. The result was a short 34-yard net punt that led to another short drive and field goal by the Bears, leaving the Saints trailing 9–0. After again moving downfield to retake the field position advantage, the Saints managed only a 29-yard punt, leaving the Bears enough breathing room to allow them to manufacture 49 yards primarily in three plays by Thomas Jones for a 16–0 lead. The Saints’ two touchdowns were the result of virtuoso clutch passing by Drew Brees. One was a brilliant display of the two-minute drill resulting in a TD connection to Colston, a 73-yard drive executed in less than a minute. The second touchdown might fairly be called the second-best Saints play ever (after the River City Miracle), given the substance of the game and the perfect timing involved—an exceedingly well-thrown ball by Brees to Reggie Bush who proceeded to stretch the field past a horde of chasing defenders, for 88 yards—the longest ever in NFC Championship play. The Saints’ defense then produced a sturdy three-and-out stand against the Bears’ offense looking to answer quickly. Surely, at that point, the momentum and the game seemed to be falling into the Saints’ favor.

What followed could only be considered a crucial chain of events. Payton and Brees again passed the Saints into control of field position and a possible scoring chance, pushing forward 53 yards in seven plays (two rushing and five passing), followed by three incompletions. Faced with increasingly wet conditions and a real opportunity to complete his team’s comeback from 16 points down, Payton elected to try for a relatively long field goal of 47 yards. Instead of using reliable but length-challenged vet Jon Carney, he turned to recently acquired former Dallas deep-kick specialist Billy Cundiff, whose stats had been a total of one miss in one attempt for the whole year. Alternatively, it is possible that Payton could have called for a punt in that situation, and thereby had a chance of pinning the Bears deep in their territory for a change. But Payton’s decision to go for the long field goal represented the philosophy that had brought the Saints to the precipice of the Super Bowl: taking every chance to score and going for it with the best execution possible. Under usual conditions, a 47-yard kick is feasible for almost any NFL kicker, especially a long-baller like Cundiff (who had hit from that distance in pre-game warm-ups), yet the attempt fell well short. A little earlier, Cundiff had followed Bush’s brilliance with an incredibly ill-timed and sloppy out-of-bounds kickoff, perhaps costing the Saints 20 yards of hardearned field position. This mistake would haunt the Saints for the rest of the half.

Once again rewarded with a short field, the Bears were able to pin the Saints deep with one of several masterful Brad Maynard punts—a 51- yarder that finished spinning at the Saints’ fiveyard line. Within the span of the next six football minutes, the Saints would suffer perhaps the only prominent mental slip of Brees’ Saints season (throwing the ball away in the face of a heavy rush in his own end zone and producing a safety), a drive-killing false start by veteran Billy Miller on their next series, and Rex Grossman’s sudden newfound ability to find his receivers. At halftime Grossman had completed three of 12 passes for a mere 37 yards, and just before the fourth quarter he had been a dismal five for 20, yet after that, he was six for six, including the game-sealing 33-yard alley-oop TD to speedster Bernard Berrian. Then, trailing 25–14, the Saints were fated to the usual results of any team trying to play catch-up ball at Soldier Field, a brutal pass rush and forced turnovers (the Saints would have two more).

All told, the keys to the loss were not in the strategy of whether to run the ball or not. Instead, they could be found in the domination of the Chicago offensive and defensive lines (the early sacks of Brees and the pressure that caused the safety, the time-eating carries by Thomas Jones and Cedric Benson, absolutely no stat line for Charles Grant, and no sacks or turnovers recorded against Grossman); the Bears’ skill in forcing turnovers (they led the league with 43 takeaways, including 20 fumbles recovered); an inability to overcome poor officiating (the Bears had no penalties with the exception of a meaningless call toward the end of the game, a near impossibility given the ferociousness of the play); and poor special teams play (missed field goals, out-of-bounds and short kickoffs). It is hard to believe that the Bears could have finished with just three conversions of 16 third-down opportunities and still win; yet it is more understandable when the reality is that the Bears started six of their 16 drives in Saints territory while the Saints started seven of their 15 drives inside their own 20-yard line.

Soon after the loss it became apparent to all of us that we would have to return to the serious task we face in rebuilding our lives and municipality. We can take solace in the fact that our football team seemed to turn a corner. It took the Pittsburgh Steelers 41 years to reach a championship game, and then two years after they were league champions and would become a dominant team for the following decade. It is entirely possible that given the head coach and corps of key players the Saints have now that they will do the same—if they build upon it. Some work is necessary (perhaps better cornerback and linebacker depth, a dangerous tightend, a new number-two wide receiver, a kicker with a longer leg but Carney’s reliability). The results of the Loomis- Payton combination this year yielded such results that the city can sincerely hope for more of the same, yet better, in the coming years.

Soon after the loss it became apparent to all of us that we would have to return to the serious task we face in rebuilding our lives and municipality. We can take solace in the fact that our football team seemed to turn a corner. It took the Pittsburgh Steelers 41 years to reach a championship game, and then two years after they were league champions and would become a dominant team for the following decade. It is entirely possible that given the head coach and corps of key players the Saints have now that they will do the same—if they build upon it. Some work is necessary (perhaps better cornerback and linebacker depth, a dangerous tightend, a new number-two wide receiver, a kicker with a longer leg but Carney’s reliability). The results of the Loomis- Payton combination this year yielded such results that the city can sincerely hope for more of the same, yet better, in the coming years.

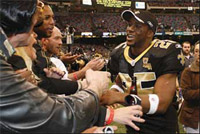

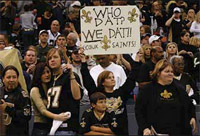

Most important, the team enjoyed its finest season in history, accomplishing what no Mora or Haslett team had even approached, not just in terms of wins and losses and reaching the conference championship, but also in terms of converting the often jaded expectations of locals into a townwide fervor of excitement and optimism. What the team meant to the city this year cannot be overstated. The Superdome was returned to an image of pride, quality and unity. New Orleanians were portrayed and embraced in a positive light around the country and were the favorite underdog in almost every footballwatching home in America outside of Cook County. New Orleanians who had not previously been football or sports fans of any kind came to partake in the macrocosm of joy, effort and spirit epitomized by the fleurs-de-lis found all over town. The symbol, emblazoned on the Saints helmet from the beginning, has slowly become a badge of passion and pride, found first in the city’s centuries-old flag but then in living rooms and on the streets. It has been carried beyond this struggling city by a team that seemed to represent its citizens’ determination to overcome a flawed past and a seemingly stacked deck. This football team carried New Orleanians’ earnest emotions into the nation’s consciousness in a powerful yet subtle way, and it was appreciated to the point of tears by many who could find no better way to manifest what they had been feeling.

Most important, the team enjoyed its finest season in history, accomplishing what no Mora or Haslett team had even approached, not just in terms of wins and losses and reaching the conference championship, but also in terms of converting the often jaded expectations of locals into a townwide fervor of excitement and optimism. What the team meant to the city this year cannot be overstated. The Superdome was returned to an image of pride, quality and unity. New Orleanians were portrayed and embraced in a positive light around the country and were the favorite underdog in almost every footballwatching home in America outside of Cook County. New Orleanians who had not previously been football or sports fans of any kind came to partake in the macrocosm of joy, effort and spirit epitomized by the fleurs-de-lis found all over town. The symbol, emblazoned on the Saints helmet from the beginning, has slowly become a badge of passion and pride, found first in the city’s centuries-old flag but then in living rooms and on the streets. It has been carried beyond this struggling city by a team that seemed to represent its citizens’ determination to overcome a flawed past and a seemingly stacked deck. This football team carried New Orleanians’ earnest emotions into the nation’s consciousness in a powerful yet subtle way, and it was appreciated to the point of tears by many who could find no better way to manifest what they had been feeling.

Perhaps the greatest lesson in any “disappointment” is that it reflects an objective not met, a meeting or goal set for a particular time not reached. As Coach Lombardi once suggested, the Saints did not fail but merely ran out of time. The mistake, or failure, was not in the effort but in the expectation that the city’s franchise would meet its destiny at this particular time. Much has been made this year, both locally and nationally, of the coincidental nature of the Saints’ fortunes and its city’s. And in that respect the fans’ disappointment in its team’s finale is only temporary, as one day the appointed time of destiny and the game plan will indeed meet their intended rendezvous. And so it is with our good city, whose citizens, like its team’s fans, must realize that any disappointment is but finite, merely subject to recognized obstacles, while its hope and faith in itself must be infinite—the necessary ingredient for overcoming them. Forty-one years? We can wait one more. As New Orleans has proved to its nation, we’re not going away; our time will come.

Perhaps the greatest lesson in any “disappointment” is that it reflects an objective not met, a meeting or goal set for a particular time not reached. As Coach Lombardi once suggested, the Saints did not fail but merely ran out of time. The mistake, or failure, was not in the effort but in the expectation that the city’s franchise would meet its destiny at this particular time. Much has been made this year, both locally and nationally, of the coincidental nature of the Saints’ fortunes and its city’s. And in that respect the fans’ disappointment in its team’s finale is only temporary, as one day the appointed time of destiny and the game plan will indeed meet their intended rendezvous. And so it is with our good city, whose citizens, like its team’s fans, must realize that any disappointment is but finite, merely subject to recognized obstacles, while its hope and faith in itself must be infinite—the necessary ingredient for overcoming them. Forty-one years? We can wait one more. As New Orleans has proved to its nation, we’re not going away; our time will come.