Arts: May 2015

Blake Boyd: The Polaroid Project: A local artist turns playfulness into an art form.

Local artist Blake Boyd has made a career of dismantling the notion of art and artist as esoterica. Boyd is soft-spoken, friendly and approachable as he explains that he’s been working on one current project for the last 10 years. Above him hangs a row of framed photographs, each face recognizable, celebrities whose faces are erupting into zombie boils, a clear homage to the schlock horror films Boyd loves.

Local artist Blake Boyd has made a career of dismantling the notion of art and artist as esoterica. Boyd is soft-spoken, friendly and approachable as he explains that he’s been working on one current project for the last 10 years. Above him hangs a row of framed photographs, each face recognizable, celebrities whose faces are erupting into zombie boils, a clear homage to the schlock horror films Boyd loves.

Boyd shows off the camera he’s used for the last 10 years to create most of the photographs in his gallery. It’s a Polaroid Macro 5, a big block of a camera, devoid of anything resembling ergonomics. The squared chunk of plastic is his favorite. “Polaroid,” he says, “was good to artists, which is why I like using it. Polaroid went out of business in 2008, but I stockpiled thousands of their film packages. Something in the chemistry of the film stock gives it its own recognizable look. This camera has been around the world with me.”

For the last 10 years he’s steadily worked on capturing as many notables as possible from New Orleans. Though most of the photographs are by design or by appointment, Boyd admits that some do arise more in guerrilla fashion, though he wouldn’t call it that. His collection contains a portrait of Brad Pitt, and it’s a beautiful rendition of the man, not the celebrity. Boyd explains that his original intention was to photograph former mayor Ray Nagin that day, but the information on Nagin’s whereabouts was always sketchy. In typical Boyd fashion, a momentary lapse in the mayor’s schedule quickly turned into a piece of art. The actor appears unposed, in stark light, head on. It’s a work of minimalism, nostalgia and playfulness. It’s pure Boyd.

References to American consumerism and pop culture abound in Boyd’s work, which lies on a continuum from Lichtenstein and Warhol, to The Polaroid Project itself, which is a fantastic concoction of meta-art, where subject and medium reference each other, producing an entirely new aesthetic — one where the artist’s audience participates as much as it beholds. Is it any wonder that Andy Kaufman is Boyd’s favorite comedian?

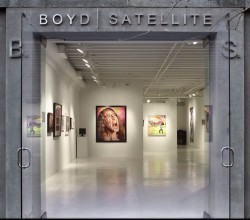

Like Kaufman, irreverence for traditional forms is part of Boyd’s charm. Since 2013, Boyd Satellite Gallery at 440 Julia Street in the Warehouse District has been the home gallery for many likeminded artists. The gallery’s manager, Ginette Bone, is an integral part in keeping its walls flowing with artwork that continues to make the Boyd Satellite Gallery an extraordinary experience. boydsatellitegallery.com

True Crime: Chuck Hustmyre takes another look at the axe man.

The history of New Orleans is steeped in the stories of scalawags, outlaws and black magic. It’s a side of New Orleans that novelist, journalist and screenplay writer Chuck Hustmyre has immersed himself in for most of his professional life, first as an ATF agent, then as a best-selling true-crime writer.

Hustmyre’s last in-depth account of crime in the Crescent City formed the basis of The Axman of New Orleans, a fictional retelling of the infamous crime spree that terrorized the city in the early part of the 20th century. Combining exhaustive research with an imaginative cast of characters, Hustmyre conjured a fascinating tale of New Orleans during the last days of Storyville and the first days of jazz.

The research for The Axman of New Orleans provided Hustmyre with unique insight into the city’s peculiar history, but the time between 1911 and 1917 is particularly interesting. It was a time when the city, and the nation, was turning from gaslight to electricity. Whether New Orleans ever did achieve anything like modernity is a matter of debate, but there is no doubt that its culture was spreading rapidly. For Storyville, where jazz music had gestated for years, the end came in 1919. The first great diaspora of jazz musicians was occurring.

Hustmyre is not a sentimental author. Crime’s currency is blood, and he won’t tell that story any other way; but the historical footnotes he discovered begged for another telling. The Axman of New Orleans was released in 2013, but, in a way, it’s still a story in development. Just recently, Hustmyre finished the screenplay adaptation of the novel and is sure that he’s captured the book’s inherent cinematic qualities. Unfortunately, while one of his screenplays — originally based in New Orleans — is being shot in Vancouver, the screenplay for The Axman story is still unrealized. The man who once solved crimes for a living finds Hollywood — East, West and South — a riddle that defies any easy explanation.

At one time during his career as an ATF agent, Hustmyre found himself being shot at in a small town called Waco, Texas. It was the final scene in David Koresh’s vision. Of course, he survived. He perseveres like the good guys in his novels persevere … because they would be foolish not to. Don’t ask him to expound on any socioeconomic theories of crime either. Criminals commit crimes because they’re criminals. It would be foolish to think otherwise. Isn’t it obvious? Will the story of the story of the axe man get the green light from Hollywood South? East? West? It would be foolish to think otherwise. Isn’t it obvious? chuckhustmyre.com

It’s in the Water – Flow Tribe: The hard-touring sextet is creating a loyal fan base, due to their legendary live shows; it seems only a matter of time before they break out nationwide.

Rhythm is primitive — more instinct than finesse — and it’s hard wired into each of us. Evolution made sure of that. Drums were the original music: summoning, warning, calling and exclaiming. The exact moment rhythm became funk is lost to us, and yet it thrives.

A good back beat and bass note puts the “crack” in what vocalist KC O’Rorke calls Flow Tribe’s “back-cracking music.” It began in 2004 when six high school graduates began to jam in backyards: five Brother Martin Crusaders and one Jesuit Blue Jay. They played sweat-soaked jam sessions in the summer heat until a sound emerged that blended New Orleans funk and an organic groove that was all their own.

For a time they separated. Some went to college, some to fight fires and another to fight in Iraq — but, little by little, the lifelong friends converged. According to O’Rorke, the rhythm and funk influences came naturally. “It’s NewOrleans, man,” he says, “it’s in the water.”

By the time manager Stephen Klein stumbled upon the band in Destin, Florida, he was convinced that they were the best live band he had ever seen. Klein, the manager of several well-known New Orleans bands, says that he’s managed a lot of bands with great live shows, but, the first time he saw Flow Tribe, it was like an out of body experience. “A Flow Tribe concert puts out enough energy to light up a city block,” he says.

Flow Tribe’s live shows have grown legendary and so has their reputation for relentless touring, yet the energy never wanes, and, as long as it doesn’t, who could blame them with the momentum they’ve built? In late 2014, they slowed just enough to get into The Parlor Recording Studio to create an album that would capture the rollicking overdrive of their live shows.

Produced by Eric Heigle, Alligator White is a solid effort by the sextet, combining funk, latin and rock influences to showcase their preternatural talent. Each member brings something unique to each track. They are a sextet with six songwriters and six different tastes, and it shows on the album.

Klein would like to see the sextet go mainstream. Certainly their talent and showmanship will have a nationwide appeal if they can write the song that brings them the right amount of airplay. Though, lots of people consider “mainstream” anathema, why shouldn’t this hard-working sextet break out? Like Klein points out, they are a band from New Orleans, but they aren’t just another New Orleans jam band. flowtribe.com