The Last Essayist

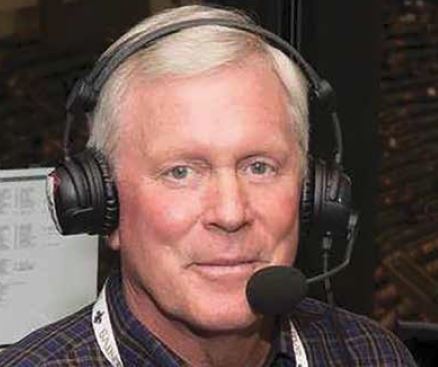

Jim Henderson retires, leaving a void in New Orleans sports broadcasting.

Any sports broadcaster who thinks that the world ends at the sideline is doing the audience a disservice. The connection that the announcer makes between the game and the people listening is the quality that defines the few greats who leave an impact from the myriad intoners who come and go across the bandwidths and frequencies over the years. In that way, without taking a peak at the landscape, one can listen and know just when and where one is just by hearing the resonance of the scene being described. Famed baseball voice men like Ernie Harwell, Bob Prince, Red Barber and Vin Scully played that role for not only their cities but also their eras. Such is the now legendary Jim Henderson, longtime radio broadcaster of the New Orleans Saints and television sports anchor, who has recently announced his retirement after having left his mark on the memories and emotions of a city often wracked with seeming misfortune, disaster and heroic yet disappointing sports franchises.

Any sports broadcaster who thinks that the world ends at the sideline is doing the audience a disservice. The connection that the announcer makes between the game and the people listening is the quality that defines the few greats who leave an impact from the myriad intoners who come and go across the bandwidths and frequencies over the years. In that way, without taking a peak at the landscape, one can listen and know just when and where one is just by hearing the resonance of the scene being described. Famed baseball voice men like Ernie Harwell, Bob Prince, Red Barber and Vin Scully played that role for not only their cities but also their eras. Such is the now legendary Jim Henderson, longtime radio broadcaster of the New Orleans Saints and television sports anchor, who has recently announced his retirement after having left his mark on the memories and emotions of a city often wracked with seeming misfortune, disaster and heroic yet disappointing sports franchises.

To understand Henderson’s impact, look no further than the person from whom he took the microphone, Hap Glaudi, as the lead sports reporter at WWL TV in 1978. Glaudi had been at WWL TV since 1964, and, like Henderson, would cover the New Orleans Saints, primarily with his post-game radio show on WWL radio. Glaudi had a decades-long connection to the sound and feel of New Orleans sports on all levels, and his essence seemed to derive from the very people he was speaking to. It was gritty, sometimes imperfect in syntax, but respectful, joyful and easy going.

Upon his arrival, from Atlanta where he had previously worked, and before that Rochester, New York, where he had been born and started his career, Henderson immediately brought a different sound and feel. It was a clear, erudite sound that seemed to speak of an urbaneness that New Orleans had long hoped to develop but probably never could. Over time, New Orleans sports fans would adopt Henderson and his punchy, descriptive deliveries into their hearts, not only loving his cool professionalism, but most especially his moments of sheer joy that broke from it, encapsulating all that a city could feel together at one moment. At those times, Henderson showed what a sports broadcaster can do best — evoke a moment in time — leaving a lasting memory in the minds of many that is far more powerful and lasting than any statue of bronze or stone.

Though beginning his radio coverage for the Saints in 1986, Henderson has been feted more recently for his memorable calls that will put fans in a certain place and time forever more: the Saints winning the Super Bowl over the Indianapolis Colts in Miami (the “pigs have flown, hell has frozen over” call after the 2009 season); the Saints defeating Brett Favre to beat the Minnesota Vikings (2009); the Saints defeating the Atlanta Falcons upon returning to the Mercedes-Benz Superdome after Hurricane Katrina (2006); and the Saints beating the Los Angeles Rams for their first playoff win (“Hakim drops the ball,” 2000). But perhaps the real work of Jim Henderson will be in the annals of his quotidian reporting of the team from his anchor desk at WWL TV and his at times dutifully weary but humorously insightful play-by-play calling for the Saints on WWL radio in the many years when any semblance of optimism seemed impossible. It was in those times, when the winning was scarce and even the most die-hard followers were at their most desperate, that Henderson really reached laureate quality, compellingly evoking each play and providing context and perspective along the way to an audience searching for meaning in the Saints’ seemingly unending struggles.

For many of those years, the ones under head coaches Jim Mora, Mike Ditka and Jim Haslett especially, Henderson was joined in a loquacious chemistry with former Saints quarterback Archie Manning, whose wit and quiet patience with the unexpected disappointments of football, forged over his own semi-tragic career as the Saints signal caller, seemed so perfectly matched with Henderson’s literary aspect.

Later Henderson would be joined in similar style by Hokie Gajan, with whom he formed an indelible, beloved and often humorous bond, and Deuce McAllister, from whose humble demeanor Henderson often drew terrific insights from his playing experience. Together these teams formed a unified concept of what New Orleans was itself in many ways — part Royal Street and part Bourbon Street, dignified and bawdy at the same time, but always elegant, even if few cared to fully appreciate it in the moment.

Gradually, they became a tradition themselves, like so many other New Orleans traditions, without anyone noticing. Fans turned down their TV audio and turned on their radio, as Henderson not only explained the details on the field but wove them into a story. Later as the franchise turned into a more frequent winner under head coach Sean Payton, there was Henderson, exhibiting the joy and the amazement of all the fans who were a part of the story. And it was always more than just about football — it was also always about New Orleans, and his love for both.