109

0

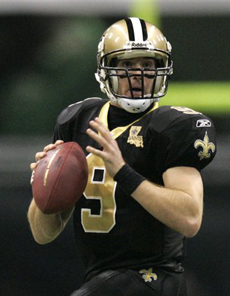

The best team in football goes for the gold

This city has been through a great deal in its 300-year-long history. Too much perhaps. But the better angels of fate have always looked over its citizens, protecting them from the ending blows of its worst demons: Wars, hurricanes and plagues have not rendered New Orleans moot or nonexistent. The people have remained, and the question always looms, Why? Why do we stay in such numbers?

This city has been through a great deal in its 300-year-long history. Too much perhaps. But the better angels of fate have always looked over its citizens, protecting them from the ending blows of its worst demons: Wars, hurricanes and plagues have not rendered New Orleans moot or nonexistent. The people have remained, and the question always looms, Why? Why do we stay in such numbers?From the beginning of the Saints franchise, in 1967, New Orleanians showed up en masse at Tulane Stadium with images of El Dorado–like fortune in their mind’s eye: After an inaugural 5–1 preseason, they witnessed John Gilliam return the opening kickoff for 94 yards against the then-vaunted Los Angeles Rams. Word is from those that were there that the sound emanating from Willow Street echoed louder than Tiger Stadium on its best night. The Saints lost that game badly and went on to have a losing season. More losses followed, lots of them. Through the Billy Kilmers and Ed Hargetts and Archie Mannings at the helm (and frequently on the turf) and innumerable head coaches and general managers, the Saints would go on to have 20 nonwinning seasons in their first 20 campaigns. And when they finally did win, mostly in the Mora years (and after Tom Benson had rescued the team from the incompetent clutches of John Mecom Jr.), and for one brief moment in the Haslett era, they witnessed gut-wrenching disappointment. Many said there was no payoff, there would be no party and no discovery of lost football treasure. After Katrina, many in America asked why New Orleans should exist, why it should be supported in the same way. But New Orleanians clung to this homespun pigskin tradition just as they held to their hope, their spirit, their homes, their land.

Led by the overlooked Drew Brees (more or less passed over by all 31 teams before signing), the 2006 Saints would go on to a glancing shot at an improbable run at the NFC Championship, followed by another disappointment, a loss. Two years wandering in the wilderness followed.

But in 2009, things changed. Belief was rewarded. Epic tales will one day be told by the city’s muses of how its representative franchise, adorned in black and old gold, traveled the path from mediocrity to perfection. For, heading into mid-December 2009, in their 43rd year, the Saints were perfect. Absolutely perfect.

This sounded, when said aloud, akin to a statement of the impossible being enunciated as fact. But much remained to be written: a slate of three games in December, including a memorably close and tough loss to the Cowboys and the ongoing quest for post-season home-field advantage; a schedule of looming January playoff foes in the powerful Vikings, Eagles, Cardinals, Packers, and/or maybe even the Cowboys again; and a possible dramatic conclusion featuring the ironic prospect of facing locals Brett Favre and Peyton Manning as part of that road or beyond.

Yet the 2009 Saints, even after tumbling to the Cowboys, have reached their own measure of a perfect season and something more. For some time now they have been the best team in football. They have set a team record for wins, grasped a playoff first-round bye, set team records for points scored and players scoring touchdowns, and almost every conceivable team standard has fallen. Not to mention that 90-year-old league records may be broken as well. The promised land is ridiculously close, like the first wafts of the land of milk and honey drifting over the hills before Canaan is seen. The Saints’, and this city’s, rendezvous with destiny, fate and reward is of all things falling on Mardi Gras. Of course. Never before has the Super Bowl fallen so close to, and in the midst of, Carnival. Naturally, this is the season in which the Saints excel.

The ingenious hero leading this charge into civic history, Drew Brees, traveled far and wide with his team, sacking the hated Falcons twice and the Panthers’ Jake Delhomme in the Dome (where Breaux Bridge’s own had never lost), the now declining but still dangerous Tampa Bay Bucs, all three teams from New York, the always smooth Philadelphia Eagles and the famous dark knight from New England, Bill Belichick, and his minions, the Patriots.

Thus, Brees and the Saints conquered many teams along the way: the whole Eastern seaboard, old rivals with which the Saints were acquainted and longstanding league leaders with whom they were not so. As in all great epics, they overcame much, including improbable come-from-behind victories against Miami when all seemed lost and Washington when destiny itself seemed to sway a kicker’s surefire game-clinching kick wide. But they also overcame injuries to both starting cornerbacks and almost half the starting defense, along with the very expectations and prognostications of defeat constantly leveled against them by the so-called “experts.”

Brees is now the captain of this city of fortune hunters who have suffered so much from the sea only to survive to see him and his fellow teammates laying their bodies and efforts on the line week after week in the Dome’s field of play, all to bring his team safely home, back from Miami, with a golden trophy.

Should they do that, one day, instead of tales of mediocrity, doom, decay and destruction that cloud this city’s memory, there will be a better tale to tell, one in which its citizens celebrate and speak of victory, of overcoming predictions of failure and becoming the best.

And there will be a Carnival to beat all the Carnivals that have ever come before. When people ask why, why do New Orleanians remain, they will have their answer, to see their belief, in themselves and for its own sake, fulfilled, and then to celebrate.