Focusing on self-defense and harmony, the discipline of Aikido provides lifelong benefits to practitionersThe word “martial” in “martial arts” derives from the name of the Roman god of war, Mars. But that doesn’t mean that all martial arts are aggressive and warlike.

According to Larry Ozenberger, the chief instructor of Aikido of New Orleans, the Japanese martial art of aikido is different.

“As a method of self-defense, the objective of aikido isn’t to inflict harm or exact revenge,” he says. “It’s simply to safely get away from a conflict or dangerous situation.”

Aikido focuses on accepting attacks and blending with them—not blocking them—thereby putting the defender in harmony with the attacker. Indeed, “aikido” is sometimes translated as “the way of harmony” (a rather odd concept for a martial art). All aikido techniques finish with a throw or a pin, but this ending is considered a neutralization of the conflict rather than a victory. While judo and taekwondo have been elevated to Olympic sports, aikido doesn’t even have tournaments. A competition wouldn’t make sense for a discipline that’s inherently noncompetitive. Because of aikido’s unique philosophy and training style, critics sometimes disparage aikido, saying that it doesn’t work.

“People who say aikido doesn’t work are trying to accomplish something else,” explains Ozenberger. “We’re not trying to learn how to prevail over other people.”

As for the “art” part of “martial art,” aikido contains an essential beauty. Its response to linear attacks is circular movements, expressed in elegant, precise pivots and flowing turns. More than a few techniques end with the attacker rolling forward or backward or flipping dramatically head over heels. Other techniques might not be as spectacular, but the core of aikido is always graceful and self-assured.

“Like with any other art, there’s so much to learn in aikido; it can easily become a lifelong pursuit,” says Ozenberger who began practicing it about 20 years ago after training in other martial arts. “The more I learn, the more I realize I don’t know. I actually sort of feel unqualified talking about it.”

Because it emphasizes constant learning as well as avoiding injury, aikido has many practitioners at advanced ages who are still engaged and training vigorously. At Aikido of New Orleans, students range in age from their teens to their sixties. Because the techniques don’t rely on physical strength, aikido is also an ideal martial art for women. “It’s for normal people, for anyone who’s reasonably healthy,” says the instructor.

Aikido doesn’t require the flexibility of a gymnast. No one is trying to kick an opponent in the head, after all. But it does develop an everyday, functional limberness. The techniques rely on the movements of the hips and torso, so practitioners develop their core strength. Improved posture and stability also result from regular training, as do better breathing habits. Reflexes sharpen, which can be attributed as much to physical practice as to the increased situational awareness that aikido develops. And naturally, all of the graceful movements, rolls and throws of aikido provide the health benefit of anaerobic and aerobic fitness. Perhaps the best health benefit of all, however, is self-defense.

“In a dangerous [situation], it’s health promoting to keep yourself safe,” Ozenberger points out. “Aikido helps you cultivate a sense of awareness about when you’re safe and when you’re not. You learn to avoid problems. Then, if there’s an unavoidable altercation, aikido increases your chances of walking away uninjured.”

Aikido is actually quite young for a martial art, dating to the 1920s. (Even in Japan, while people have heard of it, they may not be quite sure what it is.) Its techniques have antecedents in several traditional Japanese fighting arts studied intensely by aikido’s founder, Morihei Ueshiba. In his quest to find a way to live that didn’t entail triumphing over others, he began developing the martial art that eventually became aikido. His dojo (training center) in Tokyo is still active and led by his grandson, now in his fifties. And Aikido of New Orleans, being part of the U.S. federation affiliated with the original dojo and its umbrella organization, can trace a link directly back to the founder.

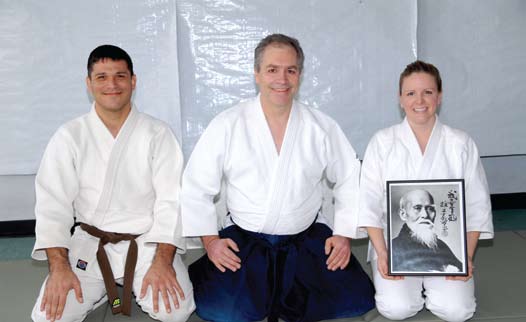

As for the dojo he leads, Ozenberger’s devotion comes from a desire to share his admiration of the art with others. Aikido of New Orleans—holding classes nine times a week Monday through Saturday at the Elmwood Fitness Center in One Shell Square—is a nonprofit organization. An attorney during the day, Ozenberger earns no money from his involvement with the dojo; neither do the other two instructors. Dues are quite reasonable, and the atmosphere is welcoming.

“It’s not my dojo,” he insists. “It’s the community’s dojo. Aikido is for everyone.”

Aikido of New Orleans’ Web site is www.aikidoneworleans.org.